The doors to 51st Division opened in late May for Doors Open Toronto. Walking home from the St. Lawrence Market with my family we stopped near the police station so my daughter could pet a German Shepherd, trained in explosives detection, panting out front. Soon we’re touring the station, a rehabilitated former foundry, and getting a lesson in policing and local history. “The park down near the Distillery,” the auxiliary officer leading our tour says, “was the location of Canada’s first parliament.” People murmur in surprise. “I didn’t know that,” my wife whispers to me. She wasn’t the only one. “That’s why it’s called Parliament Street,” the officer says, pointing in the direction of what, in another country, would likely be a national historic site: “Just down there near the lakeshore.”

The officer was partially right. The small wooden structure built at Parliament and Front streets was Canada’s first dedicated parliament building, since the first legislature was held in 1791 at an existing hall in Niagara-on-the-Lake. Our country’s second parliament was erected in the same location; the third not far away. From there it moved to Kingston and Montreal and Quebec City before Queen Victoria selected Ottawa for the permanent capital.

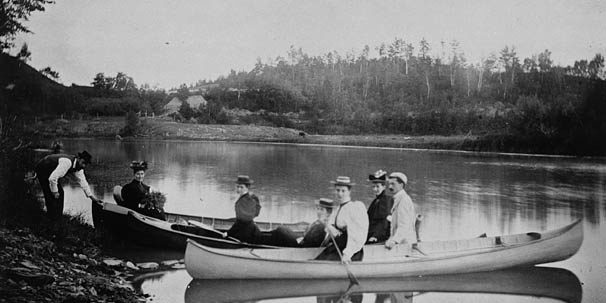

Canada 150 Ladies on the Beach

Notice a pattern? Cities strung out like ribbon along the shoreline of Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River served as home for those figuring out how to make a country from the disparate places that would become Ontario, Quebec, Canada.

Canada 150 Couple at Niagara Falls

For many who grew up in the basin (myself included), the lakes have always loomed large in Canada’s history and mythmaking. Yet despite their interconnectedness, the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes have been thought of and used in vastly different ways in telling Canada’s stories, especially in relation to the United States. In compiling thousands of writings on both waterways dating back two centuries, historians Michèle Dagenais from the Université de Montréal and Ken Cruikshank from McMaster University in Hamilton found that the St. Lawrence, the traditional entry point for French navigators, was often used as a tool to foster a sense of Canadian destiny. It looms large in myths of French and English colonial settlement. “In a country more or less lacking in national heroes,” wrote Dagenais in The Canadian Geographer, “the St. Lawrence has thus been elevated to a mythic status.”

Historically, the Great Lakes have been ‘claimed’ by the United States in most writing dating back to the early nineteenth century. If the St. Lawrence was a gateway for the movement of goods and people and the creation of cities and governments, the Great Lakes, after the completion of the Erie Canal, offered early American thinkers the same pathway to move into North America’s interior with ever-increasing speed. And as America grew up and out and militarized, the lakes, far from a unifying force, came to be seen as a buffer, capable of insulating Canada from their expansionist neighbour.

Canada 150 Canadian Lumber Don Mills

This too began to change in the early twentieth century. As relations between the Dominion of Canada and America eased, the Great Lakes became a signpost for the country’s shared responsibility as stewards of the continent. “As the century progressed,” note Dagenais and Cruikshank, “the international character of the lakes came to the fore.”

But the Great Lakes history I learned as a child, beyond ignoring centuries of First Nations life in the basin, was exclusionary and incomplete. Beginning in the 1960s, the idea of the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence as an ecological marker of Canada’s birth and development fractured how many others viewed the country’s evolution. Wasn’t the whole idea of Great Lakes dominance in our founding an extension of Eastern Canadian elitism? A kind of imperial way of thinking that downgraded other stories—First Nation, Métis, Inuit, Western Canadian, Northern, Plains—to secondary roles in how we see our significance in Canada’s creation? The pushback against this defining role for the Great Lakes occurred alongside a discovery that diversity and a celebration of multiculturalism and a flourishing of regional identities were hugely important pillars supporting what Canada is and what it could become.

That future has, in many ways, always been directed by our close proximity to water. Water that feeds us, moves us, supplies us with fresh water, dilutes our waste, ferried us to war and, for many Canadians, brought us to new homes. The Great Lakes don’t just do these things now; on the eve of Canada’s 150th anniversary, it’s crucial to remember that they’ve always provided for the continuously growing number of people who live along its shores.

Canada 150 Lake Ontario

But we can’t rely on what the Great Lakes provide us unless we hold up our end of an unspoken but vital bargain. Sewage pollution, plastic build up, urban sprawl, invasive species—these problems bedevil all of the Great Lakes. In late June, the 2017 State of the Great Lakes Report from the Environmental Protection Agency pointed to worrying trends in algal blooms, habitat loss and tainted fish still too polluted to eat in large doses. While Lake Superior is in good shape, Ontario, Huron and Michigan are in fair condition and treading water; Lake Erie, on the other hand, is getting worse.

In some ways it’s always been like this. One of the first pieces of legislation passed by the Dominion government shortly after Canada became a country was the nation’s first Fisheries Act in 1868. In curtailing overfishing, regulating how pollutants were dumped in the lakes and setting flexible fishing seasons to maintain rapidly dwindling stocks, Canadians have always known the Great Lakes must be protected from our worst instincts.

Today, that protection takes countless forms. You can petition your city council to release data about sewage overflows into the Great Lakes, replace paved front yards with grass to reduce stormwater or donate to agencies creating or rehabilitating coastal wetlands. Participate in a beach clean up day; turn off the tap; use reusable water bottles. Chances are you know a million ways to improve the Great Lakes’ health and long-term viability. What better moment than Canada’s sesquicentennial to take action.

After all, the Great Lakes basin, much like Canada, is our home.

Andrew Reeves,

Greatness/Waterlution Researcher and Freelance Journalist.